With the release of Oppenheimer in July, the nuclear bomb has taken its first tentative steps towards reconquering its share of the zeitgeist. While uncovering the torrid life of the father of the Bomb, Christopher Nolan has brought nuclear technology and its destructive power back into the collective imagination, albeit limited within the narrative space of a biopic. Reintroducing those of us born after 1991 to the reality of the Bomb is no easy task. Every era has the apocalyptic threat that defines it, and since the collapse of the Soviet Union, climate change, international terrorism, and disease have occupied the place that nuclear anxiety held steadfast for decades. Although the conflict in Ukraine, alongside tensions between the US and other nuclear powers like Iran, the DPRK and China, has reignited this fear somewhat, it is yet to return to its Cold War permeation of culture.

Oppenheimer was criticised by some for failing to depict the destruction wrought by the bombs its title character fathered.[1] In truth, this is well-trodden ground. The attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki have inspired excellent pieces of cinema by Japanese filmmakers (see the Barefoot Gen series, or Hideo Sekigawa’s Hiroshima). Beyond this, the dropping of the bombs gave birth to an international wave of ‘nuclear fiction’ that, in its earliest stage, channelled fascination with the novel technology of destruction through the stylistic forms of science fiction.[2] From the 1950s onwards, as the arms race between NATO and the Warsaw Pact accelerated, the existential threat of nuclear annihilation gave impetus to a wide range of artistic endeavours. Works of literature, music, cinema, and visual art assessed the Bomb’s capabilities of destruction, in the social realm as much as the physical. Art from this period communicated an intangible feeling of anxiety blended with morbid curiosity — a feeling which intensified as nuclear stockpiles grew and methods of bomb delivery became increasingly streamlined.

The bombs that were dropped on Japan, with the immense human effort that had gone into their development, had been seen as the pinnacle of scientific achievement. Within the decade that followed, as the race to build bigger, more destructive bombs waged on ceaselessly, they soon appeared small and primitive. The bomb on Nagasaki, the larger of the two, had a yield comparable to 20,000 tons of dynamite. Soon afterwards, bombs were developed that packed upwards of 1 megaton (million tons). By 1961, the Soviets had tested a bomb — the Tsar Bomba, the largest nuclear weapon ever created — with a yield equivalent to 50 million tons.

As Oppenheimer himself had feared, the nature of the nuclear question was transformed. No longer could anyone query nuclear power’s capacity to destroy cities; instead, society faced up to the very real possibility that it could wipe out the human race entirely. As stockpiles grew and were constantly upgraded, survival advice became obsolete as soon as it was suggested. The Duck and Cover guidance given to mid-century Americans told them they would have hours to prepare for the arrival of bombers. With the introduction of ICBMs, it would have been a matter of minutes.[3] By the mid-1980s, the world reached the peak of the arms race, with over 70,000 nuclear weapons worldwide ready for launch.[4] In spite of official efforts to play down the fear of total apocalypse, billions of people on Earth lived under what both Kennedy and Asimov had termed the ‘nuclear sword of Damocles’ – the constant awareness that they were seconds away from having their lives, homes, societies and environments irrevocably smashed into pieces.

In Britain, the danger was more acute than anywhere else. Being such a small country by landmass, the density of missile targets was (and is) the highest in the world: military and NATO bases; RAF airfields; heavily-dense cities and large towns, and centres of heavy industry and production. An attack on all, or most, of these targets would flatten most urban areas, render a huge proportion of the island uninhabitable and non-fertile from radiation, and leave enough people dead, severely injured, or displaced to cause a ‘virtual extinction of the entire nation’.[5][6] The impossibility of survival following such an attack, as well as the danger of politicians’ shortsighted egotism, form the basis of one of the most important ‘nuke films’ of all time: Threads.

ThreadsOne of the supreme pieces of Cold War nuclear fiction, of apocalypse cinema as a genre, and indeed, as many have concurred, one of the greatest films of all time, Threads is at its core a neorealist exposition of nuclear war in Sheffield. Commissioned for BBC 2 and first screened in 1984, it was written by Barry Hines, one of Yorkshire’s most formidable wordsmiths best known for A Kestrel for a Knave, and directed by Mick Jackson (who went on to direct The Bodyguard). Threads deals with the escalation of a knife-edge quarrel between East and West over oil fields in Iran, erupting into all-out nuclear war before the average civilian has taken much notice.

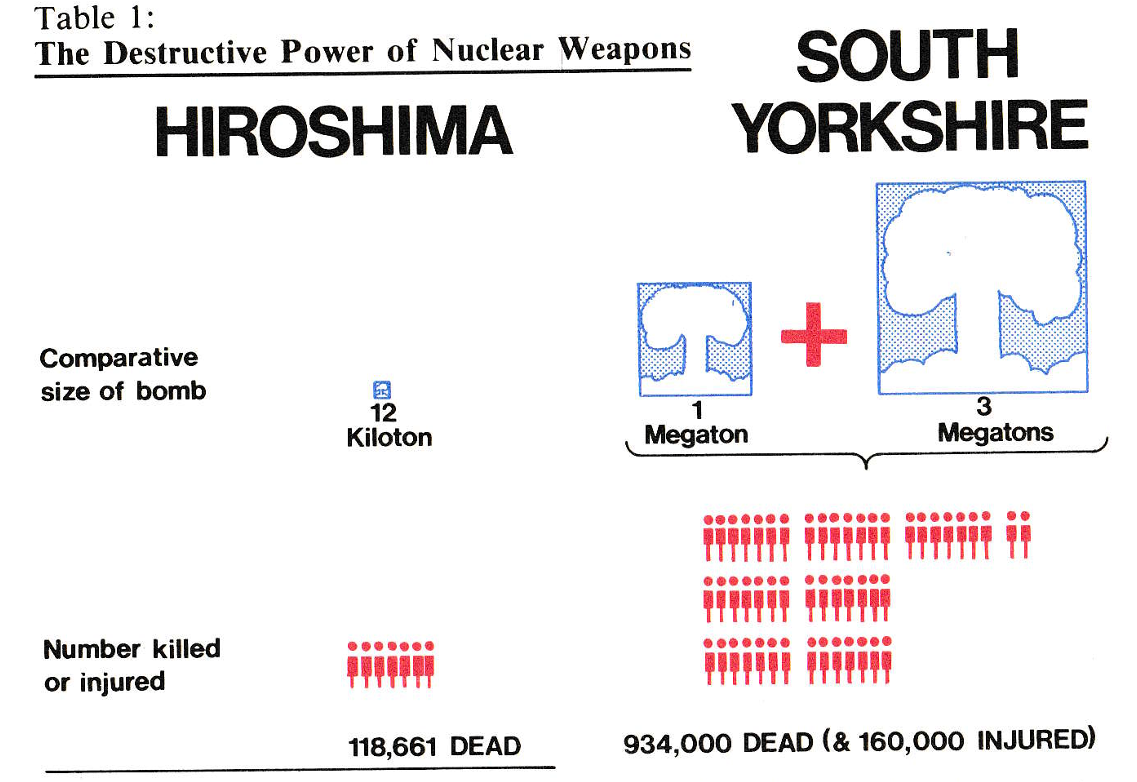

The frame of reference for the end of mankind is very narrow: the action is centred entirely within Sheffield, most of it within a small set of very ordinary characters. The choice of Sheffield was based not only on its ordinary, working-class nature as a city but also on its vulnerability to nuclear attack.[7] As a key centre for coal and steel production, with a high population and close proximity to the RAF base at Finningley (which later became Doncaster Sheffield Airport), Sheffield was regarded as a ‘prime target’ for Soviet missiles.[8] In a nuclear-planning exercise carried out in 1980, the Ministry of Defence estimated that South Yorkshire would suffer bombardment 57 times greater than that which the entire country had received during the Second World War.[9] Given all this, the left-wing city council (see James’ article from the 27th of August) were more than willing to oblige Jackson and Hines to film in the city. They recognised the danger of nuclear war and had declared the region a ‘nuclear-free zone’ in late 1980.[10] As they put it, ‘South Yorkshire would face devastation, death and injury on a scale that is almost impossible to imagine. The scale of the emergency would be such that any plans made by the Councils would be utterly futile.’[11]

An excerpt from the SY Council pamphlet “South Yorkshire and Nuclear War”, comparing the destruction in Hiroshima with the estimated effects of a Soviet attack on Sheffield and Doncaster.

An excerpt from the SY Council pamphlet “South Yorkshire and Nuclear War”, comparing the destruction in Hiroshima with the estimated effects of a Soviet attack on Sheffield and Doncaster.

Threads was subtitled ‘The closest you’ll want to get to nuclear war’, and its horrifying depiction of the Bomb, and of the grim nature of the life that follows, is well noted. However, what makes the audience so well-primed to be submerged into terror is the familiarity of the preceding drama. As the narrator foreshadows in the opening moments of the film, ‘our lives are woven together in a fabric, but the connections that make society strong also make it vulnerable.’ These interwoven threads are the basis of the plot. As Oppenheimer interweaves the Bomb into a biopic of its creator, nested within America’s scientific and political elites, Threads interweaves it into a kitchen-sink drama. In the first part of the film, we come to know the 20-something couple Ruth and Jimmy: we learn about their impending shotgun wedding amidst a deepening economic recession, and notice the undercurrent of class tensions between their families. We recognise the similarities between these deliberately very ordinary people and ourselves – as Patrick Stoddart remarked in his review at the time, the first act of the film ‘could have been Coronation Street ’.[12]

After the audience is settled in for a kitchen-sink drama, the looming threat of war encroaches very slowly in the background. Jackson and Hines put us in the perspective of the people of Sheffield, whose general apathy towards the growing threat is understandable given the more immediate personal and financial issues on their minds. As the government stocks its official bunkers, hides fire engines in places of safety, arrests ‘known and potential subversives’ and even takes valuable artworks into storage, the general public is kept in the dark about the severity of the situation. When protests for disarmament are sparked by CND (the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, which many of the cast were involved with in real life), they are met with a lukewarm-to-hostile reception. An activist issues the immortal statement, ‘You cannot win a nuclear war!’ –– in response, she is jeered and told to ‘go back to bloody Russia!’

From the civilian perspective, the worsening diplomatic situation is just one more issue causing unnecessary frustration. It puts the prices up in the shops, closes the schools, and, above all, causes a whole lot of bother over something that will probably never even happen. When it does happen, the switch from normal life to pandemonium comes as instantaneously as the first wail of the air raid siren.

Bomb The first bomb hits Sheffield.

The first bomb hits Sheffield.

Threads’ climax, the bomb scene, produces a visceral horror that traumatised an entire generation of TV viewers. Yet even as the bombs fall, the film never loses its deep embedment within the everyday, the Yorkshire everyday at that. In comparison to the Hollywood apocalypse dramas we are accustomed to, with A-list stars, million-dollar special effects, and heroic-type plotlines, Threads feels much closer to home. We hear repeated shouts of ‘Bloody hell!’ as the mushroom clouds rise, and when the blast wave arrives, BHS and Woolworths are the first buildings to be vaporised. The austere, military-style text captions that appear on screen jolt us out of participation in the terror back to the role of observers, helpless to do anything but watch an entire society reduced to ashes. ‘Nuclear exchanges escalate’, one slide blithely informs us, just before we see the entirety of Sheffield city centre consumed by a nuclear fireball.

While Hiroshima and Nagasaki were isolated attacks on cities that left the rest of Japan physically unscathed, Threads depicts all-out nuclear armageddon. The film tells us that 3000-4000 megatons of nuclear weaponry has been ‘exchanged’ in one day between East and West, with 210 megatons dropped on Britain alone. Within five or so on-screen minutes, a developed, bustling city full of workers, shoppers, children in prams, cats, dogs, and nagging grandmothers becomes a smouldering pile of bricks, with radioactive air and no running water or electricity. The knowledge that, out of shot, the rest of the Northern hemisphere will look much the same makes what the viewer sees through our limited scope even more sobering.

AfterJackson and Hines’ meticulous research and authorial skill is displayed best in Threads’ depiction of life after the attack. Every thread is frayed to pieces; almost all semblance of modern human society is eradicated. The script’s recognisable squabbles and melodramas of quotidian Sheffield life are replaced with harrowing exclamations of hopelessness and trauma, which Jackson and Hines based on studies of the psychological impact of the bombings of Japan.[13] Ruth, having tried to remain optimistic amidst the rising nuclear tensions, abandons all hope. Sequestered with her family in their basement, she laments Jimmy’s death without needing to confirm it. Unravelling, she refuses to eat even for the sake of her baby: ‘I wish it were dead. […] We’re breathing in all this radiation all the time. My baby! It will be ugly and deformed.’ On the other side of the city, Jimmy’s parents sit, heavily burned, in the blackened ruins of their home. Slowly succumbing to thirst and radiation sickness, both express envy of their presumed-dead children, saying they wish they could swap places with them. Another caption flashes onto the screen — ‘Likely epidemics: cholera, dysentery, typhoid’.

Mr and Mrs Kemp, Jimmy’s parents, step out of their shelter to search for their children.

Mr and Mrs Kemp, Jimmy’s parents, step out of their shelter to search for their children.Interspersed with the graphic horror inflicted on the people of Sheffield are scenes of the banal horror of civil-defence bureaucracy. In the bunker underneath the city hall, one of the many regional control centres set up around the country is given draconian powers over the surviving citizenry. Mid-level civil servants are suddenly charged with allocating scarce food and resources to a starving, irradiated population of their former peers. They are expected to do this while battling survivor’s guilt, panic, disorientation, the stench of their deceased colleagues crushed by debris, and the creeping awareness that they are buried under a mountain of rubble in a basement full of cigarette smoke. Their position is no more enviable than the average survivor on the ground, and, one can conclude, much less enviable than having died in the blast before you had time to feel any pain.

Perhaps the most effectively-used technique to craft the terror of life after the bomb is silence. After the bomb drops, Threads’ script is meagre: huge swathes of the film are accompanied by nothing but the howling winds of the perpetual nuclear winter. There is little conversation between any of the survivors and, in the scenes set over a decade post-bomb, language deteriorates completely to monosyllabic grunts. Language, alongside virtually all hallmarks of civilisation, has become irrelevant beyond its transactional utility in the post-nuclear barter economy. The film’s narrator, before disappearing in the second half of the film, bleakly outlines the nature of interhuman relations within this state of neoprimitivism. He diverts our grief at the sight of mass death, reminding us of the harsh truth that, as crops fail, many must die if the rest are to have food to survive.

Dave Rolinson remarks that the societal transformation wrought by the bomb in Threads is really an aggravation of the existing push towards misanthropic individualism brought by Thatcherism: ‘In place of the ‘threads’ described at the start […] there is, to appropriate Thatcher’s famous phrase, no such thing as society.’ [14] Even so, the speed with which this new order is accepted and perpetuated by the survivors is astounding. Jimmy’s heavily injured parents sit in their shelter, hearing their neighbours plead for help through the walls –– they do and say nothing. Homeowners in rural areas with multiple spare bedrooms violently refuse to shelter the displaced. The welfare state we take for granted is gone forever: hospital nurses despair at the arrival of an onslaught of injured patients, knowing they have no means to treat them.

Like the Biblical Ruth, surrounded by death, fled Moab for Judah, Threads’ Ruth eventually flees the ghost town of Sheffield on foot in a desperate search for food. As the narrator points out, food and labour are the new currencies of the ruling and working classes respectively. In parallels with the post-apocalyptic Britains portrayed in other disaster movies, such as Children of Men, the capitalist state strips back to its most basic functions: punitive violence and the control of resources and labour. Desperate people looting from the dead are summarily shot, as are those who beg for food from a heavily-guarded warehouse: ‘Who are you saving it for?’

With snark that must have irritated Thatcher if she tuned in, a chasm is dug between the government’s outdated and ludicrous projection of a manageable nuclear war and the sensory anarchy that we experience. The image of nuclear war that the Government had wished to portray is vaporised with Sheffield’s buildings — Hines and Jackson make a mockery of the idea that armageddon could be kept under control with due diligence and a stiff upper lip, with every town’s most obliging little Hitlers entrusted to keep the peace. Even the looters, detained in a makeshift holding pen in a tennis club staffed by the dregs of authority, mock the surrealism of the new order. During a protest one of them shouts, ‘I’m buggered if I’m gonna be shot by a traffic warden!’

Below ground, the bunker continues to issue communiqués about which districts to let starve, and debate the bare minimum amount of food sufficient to stop their forced labourers from dying of exhaustion, until they eventually succumb to suffocation in their airless tomb. The unifying theme of Threads’ portrayal of post-nuclear life is one of hopelessness and the impossibility of escape. The moral remains the same throughout, though it is reached by many different routes: the human race cannot survive a nuclear war.

Interned looters clamour for freedom.

Interned looters clamour for freedom.

Today

The cruel reality is that we are still very much in the firing line: Russian leadership has continually reaffirmed its willingness to attack if we are seen to intervene too heavy-handedly in Ukraine.[17] What’s worse is that in many ways we are more vulnerable than ever. Our social interactions are more reliant on electronics (which would be rendered unusable instantly), we are accustomed to much greater luxuries than people 40 years ago (all of which would be unavailable), we have no air raid sirens to warn us (not that we’d have more than 30 seconds to act either way), and the Cold War shelters have either been demolished or turned into museums. Most perilous of all, we are much less aware of the reality of nuclear warfare than those living in the 1980s, when, to official chagrin, the constant psychological threat drove membership of anti-nuclear organisations to their peak.

So, taking all that into account, why should you put yourself through watching Threads, instead of remaining blissfully naïve and hoping that the worst never comes to pass? As Karen Meagher, who played Ruth, summed it up: ‘Complacency cannot be tolerated.’[18] Beyond Threads’ merit as an incomparable work of neorealist horror, interlaced with classic Northern acerbic pessimism, its dragging of the viewer into an itching, searing awareness of the nuclear threat is a vital first step towards resisting those that downplay it. So if, as the end credits rolled on Oppenheimer, you were left with a reasonable feeling of pity for a flawed genius, treated with indubitable cruelty after making an epic contribution to scientific development, then watch Threads. You’ll curse the day he was born, then you’ll join CND.

Bibliography[1] Yam, Kimmy. “‘Oppenheimer’ Draws Debate over the Absence of Japanese Bombing Victims in the Film.” NBCNews.com, July 26, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/oppenheimer-draws-debate-absence-japanese-bombing-victims-film-rcna96279

[2] Berger, Albert I. “The Triumph of Prophecy: Science Fiction and Nuclear Power in the Post-Hiroshima Period.” Science Fiction Studies 3, no. 2 (1976): 143–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4239017

[3] Henriksen, Margot A. Dr. Strangelove’s America: Society and Culture in the Atomic Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997, 105.

[4] https://fas.org/initiative/status-world-nuclear-forces/

[5] Grant, Matthew. After the Bomb: Civil Defence and Nuclear War in Britain, 1945-68 (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 93.

[6] Openshaw, Stan, and Philip Steadman. “On the Geography of a Worst Case Nuclear Attack on the Population of Britain.” Political Geography Quarterly 1, no. 3 (1982): 263–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-9827(82)90014-3, 277.

[7] Bass, George. “How We Made the Nuclear Apocalypse TV Drama Threads.” The Guardian, January 8, 2019. https://amp.theguardian.com/culture/2019/jan/08/how-we-made-threads

[8] South Yorkshire County Council, “South Yorkshire and Nuclear War: Information for the Public in the County of South Yorkshire,” ROC Heritage, September 1984, 2. http://www.roc-heritage.co.uk/uploads/7/6/8/9/7689271/southyorksandnuclearwar1984_20161031_0001.pdf

[9] Ibid, 14.

[10] Sheffield City Council, “Sources for the Study of Sheffield and the Cold War, 1945 – 1991,” Libraries, Archives and Information, January 2013, 6. https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/sites/default/files/docs/libraries-and-archives/archives-and-local-studies/research/Cold%20War%20Study%20Guide%20v1-0%20PDF.pdf

[11] “South Yorkshire and Nuclear War”, 1.

[12] Kibble-White, Jack. “Let’s All Hide in the Linen Cupboard.” Off the Telly, September 2001. https://web.archive.org/web/20131016093924/http://www.offthetelly.co.uk/oldott/www.offthetelly.co.uk/index126a.html?page_id=1835

[13] Binnion, Paul. “Threads.” Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies, May 2003, http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/scope/documents/2003/may-2003/film-rev-may-2003.pdf

[14] Rolinson, Dave. “Threads (1984).” BFI Screenonline. Accessed September 1, 2023. http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/730560/index.html

[15] Lloyd, Harriet. “‘The End of the World as We Know It’: Futility, Fear and Film in the Age of Nuclear War.” Living with Dying, October 25, 2022. https://livingwithdying.leeds.ac.uk/2022/10/25/the-end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it-futility-fear-and-film-in-the-age-of-nuclear-war/

[16] https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15250.doc.htm

[17] Quadri, Sami. “Russia Threatens to Use Nukes If Ukraine Counter-Offensive Succeeds.” Evening Standard, July 31, 2023. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/world/russia-ukraine-nuclear-weapons-dmitry-medvedev-nato-drone-attack-b1097695.html

[18] Bass, “How We Made the Nuclear Apocalypse TV Drama Threads.”

Leave a comment