Tom White uncovers the legacy of Hull’s trailblazing anti-asbestos campaigner

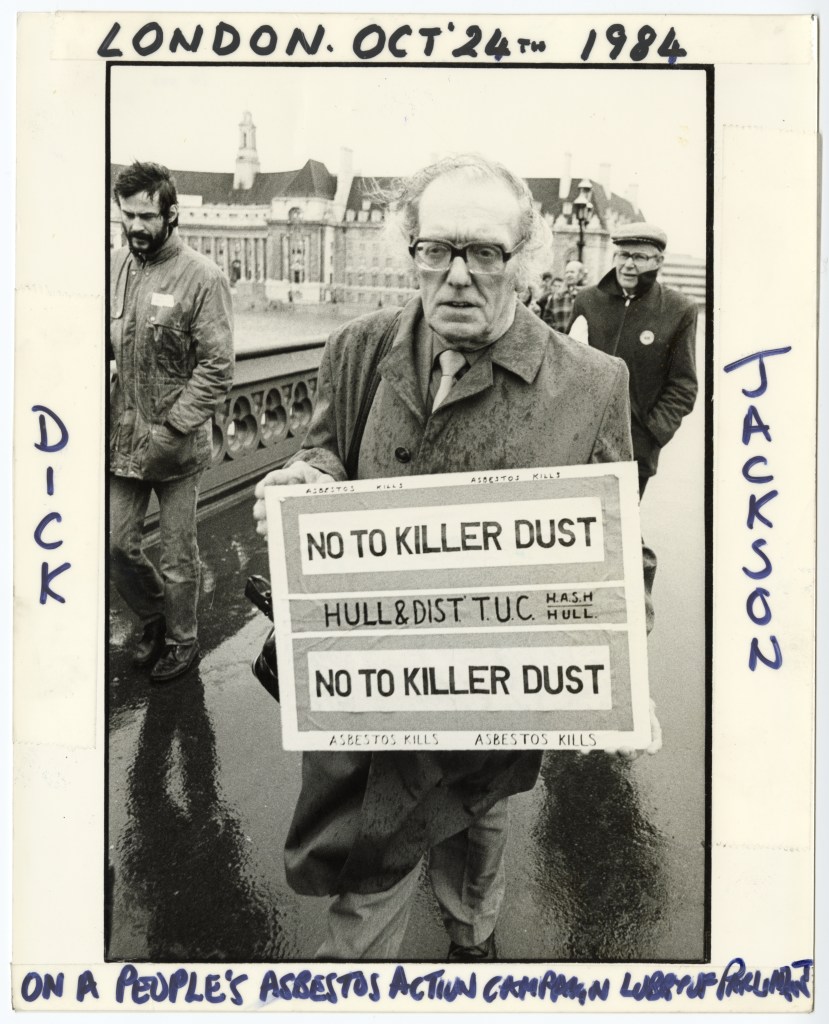

For several years during the 1980s, Hull City Council held an annual event called Volunteerarama. Local charities and voluntary groups were invited to the City Hall, where they would set up stands with information about what they did and how to get involved. At one of the tables was a figure dressed, strikingly, in pristine white overalls and a black respirator. The man behind the mask was Richard Jackson, the founder of the Hull Asbestos Action Group.

Jackson was born in Hull on May 11th, 1923. After serving in the RAF, he became an insulation engineer and worked for many years on the docks, fitting asbestos fireproofing in ships. After a spell in the construction trade, he returned to the docks in the mid-1960s. Jackson was a committed and knowledgeable safety rep for his branch of the General, Municipal, Boilermakers’ and Allied Trade Union (GMBATU). In the early 1970s he began hearing concerning stories about the material he had been working with for years.

From the early days of the industry in the late 1800s, it was apparent that asbestos work was particularly dusty and injurious. Factory inspectors observed the “sharp, glass-like, jagged nature of the particles” and their “easily demonstrated danger to the health of the worker.” Asbestosis, a debilitating and eventually deadly fibrosis of the lungs, was common. Later, it became clear that asbestos also caused lung cancer and then, at the end of the 1950s, researchers in apartheid South Africa linked the material with mesothelioma, a rare and incurable cancer that affects the lining of the chest cavity. All three diseases have a long latency period, anywhere from 15 to 50 years, and can occur after only a relatively brief exposure—there is no safe lower threshold when it comes to asbestos.

Yet the industry, which had invested heavily in the cheap and versatile material, became adept at managing information and controlling the narrative around the dangers of occupational exposure to asbestos dust. Its representatives claimed that only those who worked in certain areas of asbestos manufacturing and for extended periods were at any risk. Global production spiked from the late 1940s to the late-1970s—the companies skilfully exploited the war-time associations between asbestos, safety, and modernity, to market a growing range of industrial and consumer products. This was the age of asbestos as the “magic mineral.”

By the early 1960s, though, a handful of doctors and researchers were establishing a fuller picture of the material’s health impacts, particularly among those who were not employed in asbestos manufacturing but who regularly worked with or near the material: carpenters and joiners, builders, plumbers, electricians, plasterers, insulation engineers. British Rail replaced crocidolite—a particularly harmful type of asbestos—with fibreglass in 1967, in response to safety concerns. London dockers went on strike later the same year over the lack of safety measures when they were unloading asbestos cargoes.

Starting in the early 1970s, Jackson embarked on a programme of self-education. He corresponded with doctors and activists around the world and soon became known in his union and in Hull as an expert on asbestos. By 1973 he was calling for the material to be banned. He soon crossed paths with Nancy Tait (1920–2009) and Alan Dalton (1946–2003). Tait’s husband, William, had died in 1968 from mesothelioma, having been exposed to asbestos at work. Appalled by the industry’s conduct, she wrote a pamphlet called Asbestos Kills (1976) and later founded the Society for the Prevention of Asbestosis and Industrial Diseases (SPAID) from the kitchen of her house in Enfield. Dalton was a member of the radical science group the British Society for Social Responsibility in Science (BSSRS). In the mid-70s, he co-founded the Work Hazards Group, which soon began publishing Hazards Bulletin, a safety magazine aimed at trade union health and safety reps.

Jackson later identified 1976 as “The year of the asbestos problem.” In less than 12 months, three of his former colleagues from Hull docks died from asbestos-related diseases. Among them was his close friend, Harry Anderson. His death from mesothelioma at the age of 50 was originally attributed by the coroner to natural causes. Jackson would not accept the verdict. Armed with the latest research and the support of Tait and Dalton, he launched a years-long campaign to have Anderson’s death reclassified as the result of an industrial illness (Anderson’s widow finally received compensation in 1985).

Like Tait and Dalton, Jackson understood the full scale of this slowly unfolding disaster. But the British state and many trade union officials appeared not to. The Factory Inspectorate and its successor the Health & Safety Commission did not meaningful challenge the industry’s assertions. Several union branches organised around safety concerns and called for a ban on the material, but in the context of the steady decline of British industrial manufacturing, the national leaderships were reluctant to follow suit. It was in this context that Jackson established Hull Action on Safety and Health. The inaugural meeting took place on July 15th, 1979, at 3 Ferens Avenue, the home of the Hull University Adult Education Department. Alongside SPAID, which had been founded by Tait the previous year, and the White Lung Association, founded by a group of dock workers in California, HASH was among the first of many anti-asbestos groups.

Jackson envisaged a group that would campaign for a ban, support former workers with benefits and compensation claims, advise workers and tenants on their rights and on safe removal practices, and proactively monitor removal work being carried out in the city carried by the Council and private contractors. A room at the Adult Education Department was provided for a Resources Centre, where anyone could come and read about asbestos risks and health and safety measures. By the early 80s, concerns about environmental exposure to asbestos were growing—the material had been used extensively in schools, hospitals, and other public buildings, and in much of the council housing that had been built following the Second World War. In November 1983, Jackson was one of the attendees of the first national tenants’ and trade union asbestos conference in Nottingham. Shortly afterwards, he renamed Hull Action on Safety and Health the Hull Asbestos Action Group.

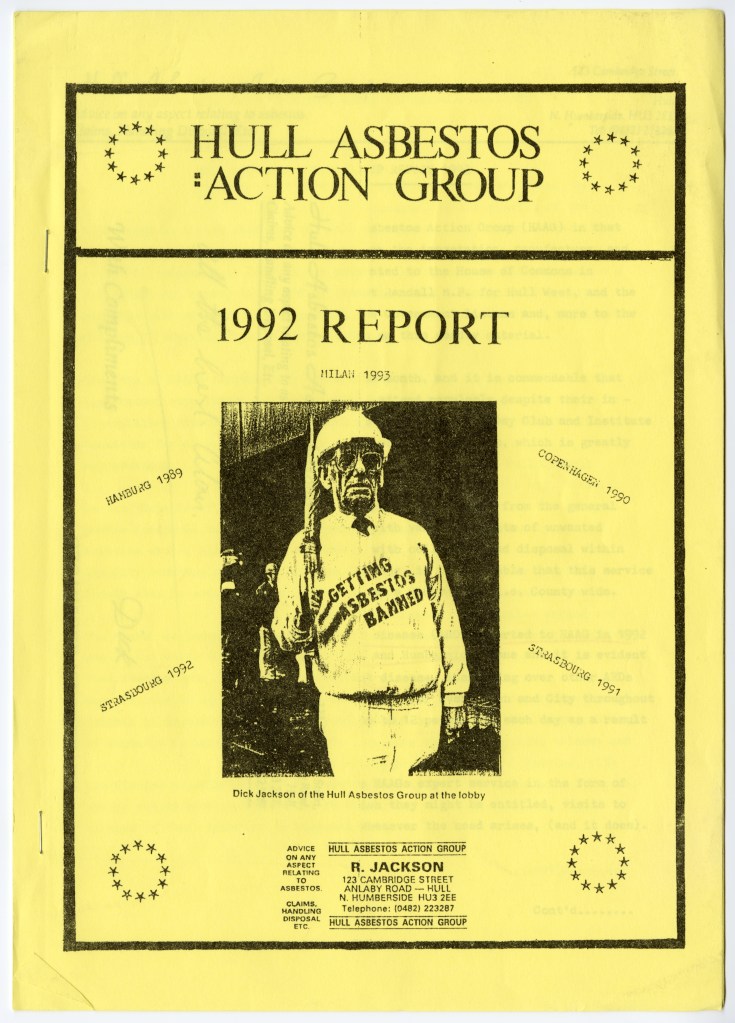

Jackson was a popular and well-respected figure. He developed a particularly close relationship with members of another of the first anti-asbestos groups, Clydeside Action on Asbestos. He was regularly invited to Glasgow to speak at meetings, sharing knowledge about how best to support those in need and how to increase awareness of the dangers of the material. He was also a keen student of approaches to anti-asbestos organising in other countries. He travelled across Europe to attend and speak at events, where he was always a recognisable figure in his matching Hull Asbestos Action Group baseball cap and sweater.

His travels culminated in a trip to Sao Paulo in March 1994, where he spoke at an international seminar organised by the Brazilian Labour Ministry and trade unions. After the decline of the asbestos trade in Western Europe in the 1980s, the industry had refocused its attention on the Global South. At the seminar, delegates agreed on three broad aims: to support victims’ struggles for benefits and compensation, to fight against the asbestos industry lobby and its misinformation, and to take action for a global ban. Jackson’s immediate energies were focused on Hull, but he understood those efforts in an international context. HAAG’s monthly meetings often included updates from trade unionists in other countries. “The World is just around the corner!” Jackson wrote in one of the group’s annual reports.

The proliferation and growth of HAAG and the other anti-asbestos groups was indicative of the broad compulsion toward mutual aid that existed in predominantly working-class areas, where everyone knew someone who had been seriously harmed by their work. The broad range of functions they came to assume was also indicative of just how far the British state had retreated from its basic functions, amid neoliberalism’s undermining of the very idea of social security.

HAAG’s history is also revealing of the challenges these groups faced to sustain themselves, particularly in the context of the broader defeats of organised labour of the 1980s, rising unemployment, and the accompanying decline in trade union membership. In his annual report for 1992, Jackson described the group’s undertakings as “extensive, expansive, [and] unique.” HAAG held monthly meetings, provided expert advice on benefits claims, and answered hundreds of queries from the public about asbestos risks and safe disposal practices. But he also bemoaned the lack of support from the local council, which “in the long term, benefit from HAAG’s activities.” Income from donations and fundraising barely covered his expenses. Many local trade union branches were still affiliated to HAAG but could not offer much by way of financial support.

Demand for the Group’s advisory services was increasing—by the early 1990s mesothelioma deaths were rising sharply—but the burden fell almost entirely on Jackson, who was by then in his early 70s. HAAG’s numbers had always fluctuated: many members were themselves suffering from asbestos-related disease, and so could only do so much, for so long. Jackson struggled to find new volunteers and became increasingly anxious about its future. “The group must not stop when the present leader stops or is unable to continue,” he wrote in the 1992 annual report. He repeated his fears in his report for 1993. It would be the last he wrote. Shortly after returning from Sao Paulo in March 1994, Jackson was diagnosed with mesothelioma.

Richard Jackson died on October 30th, 1994. In an obituary in the Guardian, Martin Wainwright noted that he had fought more than 250 compensation cases and had helped “turn the tide of industrial and medical opinion.” A few weeks after his death, the Health & Safety Executive publicly acknowledged what Jackson, Tait, Dalton, and others had always known: that official figures of asbestos-related deaths had been significant underestimates.

In the spring of 1995, the Hull Trades Council held a meeting to honour Jackson’s life and work. HAAG was revived by his daughter, Joan Ness, and a handful of other members. They kept the group going for a couple more years, but without Jackson’s energy and expertise it proved difficult to sustain. Its advisory functions were eventually taken over by the Sheffield and Rotherham Asbestos Group (now the Yorkshire and Humber Asbestos Support Group). Jackson was later awarded an honorary research fellowship by the University of Hull. But since then, he has largely slipped from the memory of his beloved home city.

It was not until five years after his death, in 1999, that asbestos was finally banned in the UK. It was a significant and hard-won victory, but had Jackson still been around he would have seen, quite clearly, what the new legislation did not contain. There was no mention of a coordinated removal programme. Nor was the ban accompanied by any real attempt to reckon with the cruel and increasingly adversarial treatment of victims, or to increase funding for research into asbestos-related diseases.

Two weeks ago, the Joint Union Asbestos Committee estimated that at least 1,400 teachers and support staff and at least 12,600 pupils have died since 1980 from mesothelioma due to asbestos exposure in schools and colleges. As the austerity-ravaged British state crumbles, more and more people are being exposed to asbestos products that are well past their intended design life. The JUAC report warned of a “tsunami” of future deaths just from exposure in education settings. “Their deaths would be the consequence of ineffective asbestos regulations and a cost-cutting culture that wrongly implies ‘asbestos is safe so long as it is not disturbed’.” The battle continues.

Tom White is a writer and further education tutor. His work has appeared in the London Review of Books, MAP Magazine, Notes from Below and the rugby league magazine Forty20. His forthcoming book Bad Dust: A History of the Asbestos Disaster will be published by Repeater next year.

Leave a reply to Arthur McIvor Cancel reply